Redefining Capacity Building for Africa in the AI Era

Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) is rapidly transforming global economies, presenting Africa with both significant opportunities and systemic risks. Despite measurable digital growth, entrenched deficiencies in education, human capital, infrastructure, and institutional capacity continue to constrain the continent’s ability to develop inclusive and future-ready AI capabilities. This article critically analyzes Africa’s digital and talent gaps within the context of a global funding landscape that increasingly prioritizes digital development initiatives. It argues that traditional, fragmented models of capacity building are inadequate for the AI era. In response, the article proposes a contextual five-pillar framework: human capital development, equitable infrastructure access, robust governance, ethical AI integration, and cross-sector collaboration. Drawing on continental policy instruments, empirical data, and global best practices, the article concludes with targeted policy recommendations to close Africa’s AI readiness gap. Ultimately, it positions strategic, adaptive, and digital-first capacity building as a cornerstone of Africa’s long-term digital sovereignty, innovation-driven growth, and sustainable development.

Keywords: Artificial Intelligence, Capacity Building, Digital Readiness, Digital Transformation, Africa

1. Introduction

The rapid advancement of AI technologies presents both unprecedented opportunities and complex challenges for Africa. The continent’s digital economy was valued at approximately $180 billion in 2023 and is projected to exceed $712 billion by 2050 (WEF, 2024). Mobile technology adoption has laid a strong foundation for further digital growth, with 44% of Sub-Saharan Africans using mobile internet services in 2023 (GSMA, 2024; Munyati, 2025). However, digital adoption requires more than connectivity; it necessitates systemic transformations in economic and social sectors, and transformative capacity building.

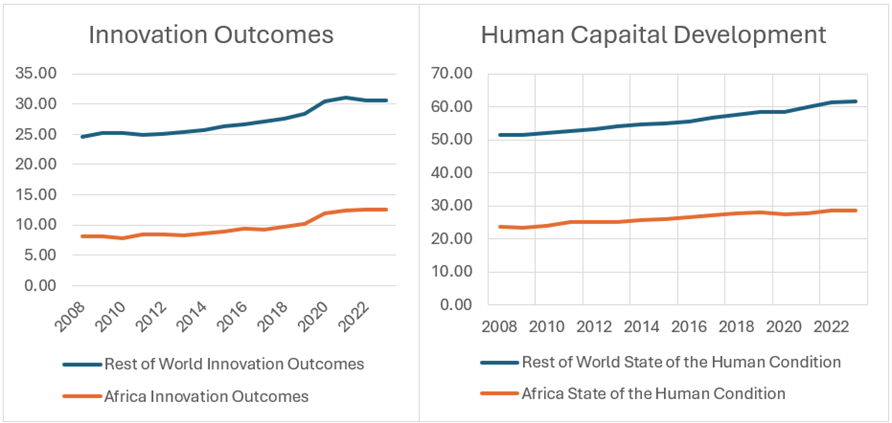

To date,Africa faces a critical and persistent digital readiness gap. The Digital Evolution Index clearly depicts Africa’s journey in digital evolution between 2008 and 2023 and how it compares with the rest of the world in achieving the desired digital readiness (Digital Planet, 2025). According to the index, although Africa has seen incremental growth in digital development over the past decade, the pace of development was slow and failed to bridge the wide gap with the rest of the world. For instance, in Innovation Outcomes that measures the degree of value captured and created from innovation, Africa’s score modestly increased from 8.13 in 2008 to 12.54 in 2023. Yet, the Rest of the World simultaneously advanced from 24.63 to 30.56, maintaining a substantial absolute gap of 18.02 points. More critically, in the State of the Human Condition that measures the population’s ability to demand and adopt digital services and the capacity for consumer spending and a fundamental pillar of digital readiness, Africa’s progress was merely 5 points from 23.81 to 28.72 in over 12 years causing the absolute gap to widen from 27.65 to 33.07 points to the rest of the world.

Similarly, in Institutional Effectiveness and Trust, Africa’s score rose from 31.22 in 2008 to 34.70 in 2023, yet the gap with the Rest of the World remained largely stagnant at approximately 17 points. Overall, Africa’s digital readiness score in 2023 was merely 34 out of 100, significantly below the global average of 62.1 (Digital Planet, 2025). Africa’s top performers, such as Kenya and Rwanda reached maximum scores of only 35.5 and 34.6, respectively, significantly trailing global frontrunners like Singapore (94.1) and the UAE (89.4). Most of the other countries, including Ethiopia, Sudan, and Chad, remained below a score of 20 in 2023, underscoring persistent digital stagnation and the urgent need for systemic intervention.

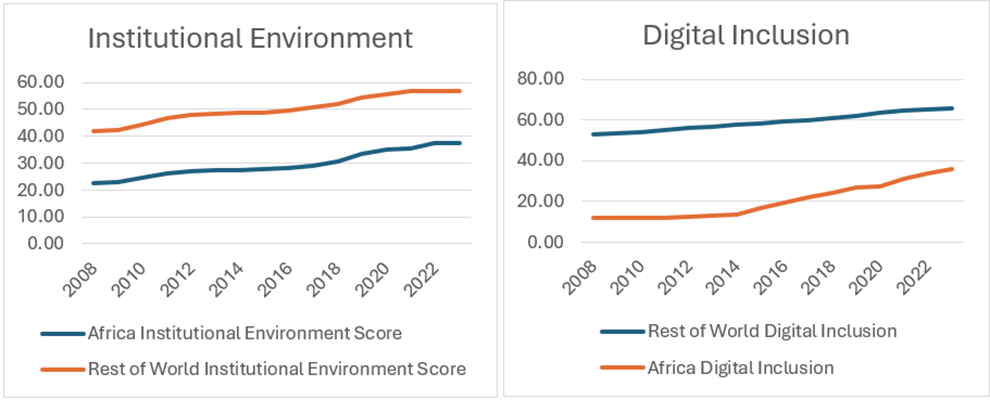

The digital evolution index also reveals that the institutional environment and digital inclusion are also showing huge gaps with no sign of closing the gap when compared to the rest of the world, as shown in chart below.

Addressing these profound digital evolution gaps and deceleration in key developmental metrics critically depends on comprehensive capacity-building efforts centered on infrastructure development, institutional and human capital development. Africa’s demographic profile is characterized by a youthful population, with nearly 60% under the age of 25, offering a unique advantage (WEF, 2023). However, this potential demographic dividend can only be realized if young Africans acquire relevant AI and digital skills. Recognizing this imperative, the African Union’s Continental Strategy for Artificial Intelligence identifies human capital development as fundamental for AI development and adoption, advocating for wide-ranging institutional reforms and workforce training aligned with industry needs (AU, 2024).

2. AI’s Promise: New Roles, New Demands

Artificial intelligence is transforming global economies and social systems by automating routine tasks, enhancing data-driven decision-making, and generating entirely new categories of jobs. In the African context, AI is being deployed across critical sectors such as fintech, agriculture, healthcare, and public services. However, each application area introduces specific skill demands that go beyond general digital literacy and sectorial knowledge, requiring advanced digital and AI skills.

- In the fintech sector, AI-powered credit scoring, fraud detection, and risk modeling are expanding financial inclusion by enabling access to banking services for previously unbanked and underbanked populations (FSD Africa, 2024). The development and deployment of these solutions require specialized competencies in machine learning, data analytics, and cybersecurity, underscoring the need for workforce training that integrates both technical proficiency and sector-specific regulatory knowledge.

- Agriculture remains the primary source of employment for over 60% of Africa’s workforce (FAO, 2023), making it a priority sector for AI integration. AI-driven precision agriculture techniques—including satellite imaging, remote sensing, and predictive analytics—are being used to optimize irrigation schedules, monitor soil conditions, detect pests and diseases, and forecast crop yields. These tools have achieved up to 92% accuracy in pest and disease detection (Elbehri & Chestnov, 2021), and have been shown to increase crop yields by more than 22% (Hossain & Islam, 2022). However, leveraging these gains at scale will require the development of AI-literate agricultural extension workers and rural digital infrastructure.

- The healthcare sector is undergoing significant transformation through the adoption of AI-assisted diagnostic tools, which enhance both the speed and accuracy of disease detection. For example, AI-powered medical imaging systems have reduced diagnostic timeframes while achieving accuracy rates exceeding 95.5% (Yang et al., 2025). These advances demand upskilling healthcare professionals with new technical competencies, including proficiency in clinical data interpretation, system calibration, and the ethical use of patient data within AI-enabled environments.

A particularly transformative development is the rise of agentic AI systems, autonomous entities capable of executing tasks and making decisions without human intervention. These systems create new labor market demands, especially in roles involving AI system oversight, algorithmic auditing, ethical risk management, and regulatory compliance (AfDB, 2024). These trends indicate that African labor markets will require a broad spectrum of AI-related competencies, ranging from foundational digital literacy to advanced AI engineering, governance, and regulatory skill sets.

3. Africa’s Talent Challenge

Africa’s capacity to leverage the transformative potential of AI is hindered by a complex, multi-layered talent deficit. This challenge extends beyond the limited number of trained professionals and reflects deep structural issues ranging from the quality and relevance of education to disparities in digital infrastructure, institutional maturity, and socio-economic inequality.

A core component of this challenge lies in the continent’s educational systems. Although university enrollment has expanded in recent decades, curricula often lack the quality, relevance, and practical orientation necessary to prepare learners for AI-driven economies. Only 12% of African universities currently offer accredited programs in AI or machine learning, compared to nearly 90% of institutions in North America and Europe (UNESCO, 2023). Moreover, a small subset of these institutions provides comprehensive AI programs that incorporate essential components such as practical skills, ethical reasoning, and data governance (AI4D Africa, 2024).

Universities’ curricula also frequently lag behind industry requirements, with limited focus on applied skills including programming, data labeling, and AI system integration. This skills gap is also evident in broader literacy trends. According to UNESCO (2023), digital and ICT competencies remain critically limited, especially in non-urban areas. This deficit is reflected in the Human Capital indicator of the Digital Evolution Index. In 2023, the regional Human Capital score for Africa averaged just 33.8 well below the global average of 64.7 out of 100. Countries such as Nigeria and Ethiopia scored 28.5 and 26.3 respectively, underscoring severe deficiencies in digital competencies and readiness for AI-aligned employment (Digital Planet, 2025). As a result, there remains a severe shortage of professionals with the necessary competencies to develop, deploy, and govern AI systems at scale.

Disparities in digital infrastructure significantly worsen the skills gap. While urban centers have made measurable progress, rural and peri-urban areas remain chronically underserved. As of 2024, only 23% of rural Africans and 57% of urban residents had access to and regularly used the internet (ITU, 2023a).

In terms of mobile broadband, 4G coverage reaches 93% of urban populations and only 43% of rural communities in Africa, well below the global averages of 98% and 80%, respectively (ITU, 2024). UNESCO (2023) reports that only 33% of rural schools in sub-Saharan Africa have access to electricity, limiting their ability to adopt and benefit from digital learning tools. In many rural secondary schools, student-to-computer ratios often exceed 30:1, with some cases reaching as high as 50:1., compared to much lower ratios in urban schools (World Bank, 2023).

Furthermore, digital skills deficits remain a critical barrier for rural youth, impeding their ability to engage in online education or access AI learning platforms. For instance, 78% of youth in Nigeria lack basic digital literacy skills, while less than half of teachers in Zimbabwe possess fundamental ICT competencies, limiting effective digital education in rural areas (UNICEF Nigeria, 2025; UNICEF Zimbabwe, 2024). Without these foundational competencies, advanced AI training is inaccessible to large segments of the population ultimately limiting the pool of individuals who can engage meaningfully with AI.

Retaining skilled talent poses another major challenge. Africa continues to face a persistent brain drain, with highly trained professionals migrating to more developed economies in search of better compensation and career advancement. According to the African Development Bank, the continent loses more than $2.6 billion each year due to the emigration of highly skilled professionals particularly in the medical, digital, and engineering fields (AfDB, 2024). This outflow trend continues to intensify annually, depleting local innovation capacity and weakening efforts to build resilient AI ecosystems in the continent. The brain drain not only undermines local innovation ecosystems but also slows the rate of digital adoption in key economic and social sectors that could elevate millions out of poverty.

Encouragingly, despite the persistent brain drain, there is a strong inclination among the African diaspora to contribute to the continent’s development. For instance, a 2019 study by Agence Française de Développement (AFD) found that 70% of African MBA students expressed a desire to return to Africa (AFD, 2019), reflecting a broader sentiment among highly skilled professionals. While a precise figure for diaspora AI professionals specifically is not readily available, it is evident that a significant portion would consider returning to the continent, provided there are improvements in living conditions, research infrastructure, funding access, and political stability. Africa’s talent challenge is systemic and requires holistic interventions that address economic challenges, infrastructure development, and talent retention strategies. This compound issue demands a more coordinated and harmonized continental intervention rather than state-level approach. Isolated national initiatives are unlikely to close the continental AI skills gap or enable Africa to realize the full economic and developmental benefits of AI.

The above-mentioned barriers, educational misalignment, infrastructural exclusion, and persistent brain drain, are interrelated symptoms of a systemic deficiency. Addressing them requires integrated and multi-level policy responses anchored in a shared continental vision.

4. A Five-Pillar Framework for AI-Capable Workforce in Africa

Creating an AI-ready workforce in Africa demands a strategic, integrated, and context-sensitive approach that responds to the continent’s structural realities. A foundational policy anchor is the Nairobi Declaration on AI Education (2024), a continent-wide agreement that emphasizes the early introduction of computational literacy in schools, targeted capacity development for educators, and inclusive planning of digital infrastructure to support AI learning ecosystems. Unlike standardized global frameworks, the Nairobi Declaration acknowledges the socio-economic diversity across African countries and promotes interventions that are explicitly designed to ensure accessibility, contextual relevance, and long-term systemic resilience. Its emphasis on practical workforce development makes the Declaration particularly relevant to Africa’s rapidly growing youth population and expanding digital economies, which together offer a unique opportunity to embed AI literacy at scale.

Global best practices, such as competency-based education models (UNESCO, 2023) and the Triple Helix innovation theory (Etzkowitz & Leydesdorff, 2000), inform the following five interrelated pillars to build an AI-ready African workforce:

4.1 Human Capital Development and Lifelong Learning

According to human capital theory, sustained investment in education and workforce development is essential for productivity and long-term economic growth (Becker, 1994). In the context of AI, this investment must extend across the entire learning continuum from foundational schooling to lifelong, adaptive reskilling systems that can respond to rapidly evolving technological demands. As technological change accelerates, the average shelf life of technical skills has significantly declined. Many current skills may become obsolete within three to five years, necessitating robust institutional mechanisms for continuous upskilling and timely acquisition of new competencies. Recent industry assessments suggest that many technical competencies retain their market relevance for only five years, with some AI-related skills becoming outdated within as little as thirty months. This rapid turnover demands that individuals and institutions institutionalize regular upskilling cycles to remain competitive in dynamic labor markets. Therefore, lifelong learning has shifted from being a desirable goal to a foundational necessity for any future workforce strategy (WEF, 2020).

Restructuring Africa’s educational systems is a prerequisite and urgent task that requires embedding flexible, competency-based learning pathways that span formal schooling, technical and vocational education, and continuous in-service training. These pathways must be adaptable and aligned with evolving labor market needs. As AI evolves, the half-life of skills continues to shrink, requiring sustained, adaptive learning opportunities.

The Nairobi Declaration advocates for the early integration of computational thinking, digital literacy, and ethical reasoning into national curricula, beginning at the primary education level to build foundational AI capacity. This equips learners not just with technical proficiency but with the problem-solving mindsets needed to engage meaningfully with AI. UNESCO’s Global Education Monitoring Report (2023) further reinforces this by emphasizing critical thinking and interdisciplinary learning as core enablers of future-oriented education.

4.2 Ecosystem Approach to Skills Development

Developing AI skills cannot rely solely on educational reform. It requires an ecosystem-wide approach that fosters collaboration among education providers, industry leaders, public institutions, and civil society organizations. The Triple Helix theory emphasizes dynamic interactions among universities, industry, and government as drivers of knowledge creation and economic development (Etzkowitz & Leydesdorff, 2000). In practice, this involves creating structured partnerships that support:

- Co-designed curricula aligned with labor market needs.

- Internships and apprenticeships that bridge the gap between theory and practice.

- Research collaborations that serve as pipeline to employment & innovation.

Recent data from the Digital Evolution Index 2025 reinforces the importance of this ecosystem approach in Africa. Countries like Kenya and Nigeria, which rank highest in Innovation Momentum among African nations (Kenya: 52.6; Nigeria: 50.9), demonstrate how strong collaboration across academia, government, and private sector actors correlates with the rapid emergence of AI startups, research labs, and patent filings. Similarly, Mauritius and South Africa, with strong Institutions and Business Environment scores (Mauritius: 61.3; South Africa: 58.7), have seen a rapid expansion of public-private partnerships and industry-driven AI training programs. These cases illustrate that robust ecosystem linkages are a critical determinant of progress in AI talent development and innovation capacity (Digital Planet, 2025).

4.3 Digital Infrastructure and Access as Enablers

Foundational infrastructure remains a prerequisite for AI skills development. In the absence of equitable access to high-speed internet, affordable computing devices, and stable electricity, efforts to expand AI literacy risk excluding vast segments of the population, particularly in rural and underserved regions. Therefore, infrastructure development must be pursued in parallel with human capital investment to ensure that digital transformation is both inclusive and scalable. International and continental institutions such as UNESCO and the African Union emphasize that infrastructure development should be fully embedded within national education, innovation, and workforce development strategies to avoid reinforcing digital inequality.

The World Bank’s Digital Economy for Africa initiative further reinforces the necessity of robust digital infrastructure as an essential pillar for leveraging the digital economy for development, including expanding education for rural and underserved communities (UNESCO, 2021; African Union, 2020; World Bank, 2021). According to the Digital Evolution Index, digital inclusion remains critically low across most African nations. As of 2023, 28 out of 34 African countries scored below 30 out of 100 on the digital inclusion scale, with countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, Niger, and Chad scoring under 20. These scores highlight not only insufficient connectivity, but also entrenched barriers related to affordability, digital literacy, and user experience (Digital Planet, 2025). Furthermore, governments should establish and enforce minimum digital infrastructure standards for schools, including internet bandwidth thresholds, appropriate device-to-student ratios, and access to cloud-enabled AI learning environments. Such infrastructure guarantees are essential to support inclusive digital growth and to mitigate the widening of existing educational and technological inequalities.

4.4 Policy and Governance Frameworks

Robust policy and regulatory frameworks are essential for coordinating AI workforce strategies and for aligning national skills development efforts with broader socio-economic transformation goals. Countries with relatively stronger institutional capacity and business environments, such as Mauritius and South Africa, are beginning to establish more cohesive AI ecosystems characterized by active public-private collaboration, targeted investment and trust, while the rest of African countries exhibit largely underdeveloped, fragmented, and uncoordinated (Digital Planet, 2025). To this effect, the recently adopted Continental AI Strategy provides guiding principles to member states to build successful AI ecosystems. It prioritizes harmonized governance and ethical frameworks, building AI capabilities through education and research, and investment and cooperation to collectively leverage AI for sustainable socioeconomic growth and global competitiveness.

To drive coherent implementation of the strategy, countries should establish dedicated national task forces on AI skills and workforce development, with representation from government ministries, regulatory agencies, industry bodies, and civil society. The taskforce shall:

- Monitor, coordinate and oversee national efforts.

- Harmonize cross-sector collaboration

- Facilitate public-private partnerships.

- Align AI capacity goals with broader development agendas.

Institutional effectiveness is also a critical enabler of AI readiness. In 2023, most African countries recorded effectiveness and trust scores below 40, with an average of just 29.7 far below the global average of 65.6. This institutional challenge not only harm AI ecosystem development but also the ability to coordinate cross-sectoral capacity development (Digital Planet, 2025). Furthermore, Governments should also employ targeted policy instruments such as tax incentives, innovation grants, and research subsidies to encourage private sector engagement in AI skills development and training initiatives.

4.5 Ethical and Responsible AI

The ethical governance of AI is now widely acknowledged as a foundational requirement for ensuring that digital transformation in Africa is inclusive, rights-based, and sustainable. As AI systems are integrated into critical sectors such as healthcare, education, agriculture, and finance, concerns related to data privacy, algorithmic bias, and transparency are intensifying, particularly given the continent’s diverse legal traditions and cultural contexts (AU, 2024; UNESCO, 2023). Almost all AI solutions currently deployed in Africa are developed externally and often rely on datasets that lack local knowledge and contextual relevance. This increases the risk of producing inaccurate, biased, or socially misaligned outcomes (AI4D Africa, 2024).

The global debate on AI ethics has produced a range of principles, such as transparency, fairness, accountability, and respect for human rights, that are now widely recognized as essential for responsible AI (Jobin, Ienca, & Vayena, 2019). While global ethical principles such as transparency, fairness, and accountability offer a useful foundation, effective AI governance in Africa must adapt these frameworks to local sociocultural, legal, and economic contexts in order to ensure legitimacy, acceptance, and relevance. Adapting these high-level principles into actionable guidelines and enforceable standards remains a challenge for many African countries, particularly in countries with limited policy development capacity or weak institutional oversight (AfDB, 2024).

While the African Union’s Continental Strategy for Artificial Intelligence (AU, 2024) and UNESCO’s recommendations (UNESCO, 2023) emphasize the importance of ethical AI, implementation is uneven, and few countries have established dedicated frameworks or oversight mechanisms.

Addressing these challenges requires a multi-pronged approach. First, there is a need for greater investment in local research and capacity building on AI ethics, including interdisciplinary collaboration between technologists, social scientists, policymakers, and civil society. Embedding AI ethics within formal education systems, technical training programs, and professional development pathways is essential to ensure that future practitioners are equipped to anticipate and manage ethical risks (UNESCO, 2023). Second, regional collaboration through the African Union and networks such as AI4D Africa can help harmonize standards, share best practices, and address cross-border ethical and regulatory issues (AI4D Africa, 2024). Finally, public engagement and stakeholder consultation are critical to ensure that ethical frameworks reflect the values and priorities of African societies and build trust in AI systems.

Promoting ethical and responsible AI use in Africa requires more than technical fixes or regulatory mandates. It demands sustained public engagement, investment in ethical capacity building, and a deliberate effort to align technological development with African values and social priorities.

5. Redefining Capacity Building in the Age of AI

Capacity building is undergoing a profound and irreversible transformation, driven by digitalization and the need for agility. How individuals, organizations, and societies build and enhance their capabilities has shifted. Traditional approaches to strengthening individual, organizational, and systemic capabilities are increasingly misaligned with the speed and complexity of change in today’s digital environment. These models are typically characterized by long-cycle programming, resource-intensive operations and limited scalability, no longer meet the demands of fast-evolving technological and economic conditions (UNDP, 2021).

In contrast, emerging approaches prioritize scalability, adaptability, sustainability, and digital-first interventions, enabling capacity development strategies to operate more efficiently and inclusively across diverse environments. Digital platforms facilitate rapid and targeted upskilling by leveraging microlearning modules, adaptive content systems, and real-time learner feedback. These tools allow individuals to acquire relevant skills regardless of their location or prior exposure to formal training systems. At the organizational level, digital transformation empowers institutions to modernize their internal processes, enhance the efficiency of program design and delivery, reduce operational costs, and expand their reach through integrated communication, outreach and fundraising systems. Digitally enabled capacity-building models are more responsive to local contexts and are highly scalable, offering significantly lower marginal costs and faster deployment timelines compared to conventional approaches.

This paradigm shift is reinforced by fundamental changes in global development financing. Over the past decade, leading development institutions have increasingly prioritized digital initiatives, reflecting a growing consensus that digital transformation is central to achieving inclusive, resilient development outcomes.

Between 2015 and 2020, the World Bank supported 701 grant projects worldwide, including 81 that were digital initiatives, amounting to approximately $1.07 billion. This trend accelerated in the 2020–2025 period, with the number of global grants to digital initiative was more than doubled, rising by 101.23% to 163 projects. Concurrently, funding for these digital projects saw a substantial increase of 167.95%, reaching approximately $2.87 billion. This indicates a clear strategic pivot towards digital transformation.

The shift toward digital transformation is even more pronounced in Africa. The number of digital projects in the region nearly doubled, rising from 24 between 2015 and 2020 to 47 between 2020 and 2025. Funding for these digital initiatives grew dramatically by approximately 403.78%, reaching $1.60 billion from $318.04 million. By 2025, digital initiatives accounted for 20 percent of all approved World Bank projects in Africa and represented 32 percent of total regional grant value, indicating a strong policy preference for digital initiatives (World Bank, 2025).

| Scope | Metric | Period Range | Absolute Change | % Change | |

| 2015–2020 | 2020–2025 | ||||

| Global | Total Projects | 701 | 643 | -58 | -8.27% |

| Total Grant Amount (USD Billions) | 11.35 | 33.90 | 22.54 | 198.52% | |

| Digital Projects | 81 | 163 | 82 | 101.23% | |

| Digital Grant Amount (USD Billions) | 1.07 | 2.87 | 1.80 | 167.95% | |

| Africa | Total Projects | 246 | 235 | -11.00 | -4.47% |

| Total Grant Amount (USD Billions) | 3.04 | 5.01 | 1.97 | 64.78% | |

| Digital Projects | 24 | 47 | 23 | 95.83% | |

| Digital Grant Amount (USD Billions) | 0.32 | 1.60 | 1.28 | 403.78% | |

Table 1: World Bank Grant Project Trends: Global and Africa (2015–2020 vs. 2020–2025). Source: World Bank (2025)

Note: Data includes both active and closed projects. Filtered by Theme Level 3 categories: FY17-E-gov, FY17-ICT policies, FY17-ICT Solutions, FY17-Innovation & Tech Policy, and FY17-Sci & Tech. Time periods covered are January–June 2015 to June 2020, and June 2020 to June 2025.

This trend is further reinforced by high-level strategic commitments from bilateral partners, multilateral agencies, and private sector firms. Initiatives such as Italy’s €5.5 billion Mattei Plan for Africa strongly focuses on digital infrastructure, and human capital development, in key sectors like economy, agriculture, energy, health, and education, with over $100 million already committed to digital readiness programs in countries such as Mozambique, Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire, and Ghana (Fattibene & Manservisi, 2024; GC3B, 2025).

Private sector firms are also scaling up AI and digital workforce investments. Fortinet, for example, has pledged to train one million individuals globally and 42,000 cybersecurity professionals in Africa by 2026 (APAC Media, 2024; GC3B, 2025). On the continental level, the African Union Development Agency (AUDA-NEPAD) is preparing to launch AI training program aimed at reaching one million learners across Africa by 2025 (AUDA-NEPAD, 2024). Additional initiatives by Microsoft, Cisco, Vodacom, and others aim to provide AI and other digital skills training opportunities to millions of African youths (Microsoft, 2025; Boltt, 2025; Africa News Agency, 2025; Ecofin Agency, 2024; EngineerIT, 2023).

For institutions engaged in capacity development, such as the African Capacity Building Foundation (ACBF), a specialized agency of the African Union, the message is clear. To remain effective and relevant, capacity-building strategies must prioritize digital initiatives, digital-first design, and the integration of technology across all sectors and functions, regardless of the specific capacity domain being addressed. This requires redefining capacity building principles and business models to design and deliver transformative and sustainable digital capabilities. Such a strategic repositioning is not optional but essential to attract funding, deliver measurable impact at scale, and support Africa’s transition into a digitally empowered, resilient, and innovation-driven prosperous continent.

6. Recommendations

To build a continent capable of thriving in an AI-driven economy, African governments and development stakeholders should adopt a coordinated set of actions that address structural gaps and scale up inclusive capacity-building efforts.

- Reform education systems to integrate AI literacy and computational thinking from early childhood grades through to tertiary education. These reforms should draw from globally tested frameworks that are adaptable to Africa’s diverse social, economic, and linguistic contexts (OECD, 2025; Adu, 2025; WEF, 2025).

- Commit substantial national resources to digital infrastructure development including setting up training hubs, incubations centers, and equipping schools with essential digital services. This includes directing portions of national budgets to enabling digital access in rural communities (AU, 2020; World Bank, 2021; ITU, 2023b)

- Introduce targeted incentive programs including tax exemptions, research grants, and startup capital to encourage skilled professionals in the diaspora to return and contribute to domestic innovation ecosystems, aligned with the African Union’s Brain Gain Initiative.

- Create dedicated national agency to oversee AI governance, including compliance with the African Convention on Cybersecurity (2023), promotion of ethical standards, and harmonization of public and private sector AI deployment practices.

- Facilitate structured public-private partnerships to align academic curricula with evolving industry demands, expand apprenticeship programs, and strengthen national AI innovation ecosystems through joint research and resource sharing.

- Develop a continental AI and Digital Capacity Evolution Index modeled after the Digital Evolution Index to track national and regional progress in areas such as human capital, infrastructure, institutional governance, and digital inclusion. The index should be updated periodically to inform policymaking, funding decisions, and regional cooperation.

7. Conclusion

Africa’s future in the age of artificial intelligence will be determined by the choices it makes today. The continent has made progress in digital access and innovation, but structural gaps in education, infrastructure, and institutional readiness continue to hold back inclusive growth. These challenges are not isolated. They are widespread, deeply interconnected, and demand deliberate, timely, and coordinated interventions from all stakeholders.

To unlock the benefits of AI, investments must focus on strengthening human capital, expanding equitable infrastructure, and building governance systems that support innovation at scale. African institutions must also become more agile and responsive to the demands of a fast-changing technological landscape. These priorities must be advanced through a new approach to capacity building, one that is digitally anchored, inclusive, and responsive to evolving technological and socioeconomic dynamics. This rethinking is essential to ensure that efforts are sustainable and relevant across the continent’s varied contexts.

The task ahead is not just about catching up with the rest of the world. It is about creating a foundation for Africa to lead in shaping technologies that align with its values and development goals. This is not a short-term agenda, but a long-term commitment that will define Africa’s place in the global digital future.

8. References

- Adu, I.E. (2025). Integrating computational thinking and ai in early childhood education using holistic STEM framework, Advances in Educational Technologies and Instructional Design, pp. 65–96. doi:10.4018/979-8-3693-6210-5.ch003. https://www.igi-global.com/chapter/integrating-computational-thinking-and-ai-in-early-childhood-education-using-holistic-stem-framework/361662

- AfDB. (2024). Keynote speech delivered at the 15th bi-annual General Assembly and Scientific Conference of the African Academy of Sciences (AAS)… https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/speeches/keynote-speech-delivered-15th-bi-annual-general-assembly-and-scientific-conference-african-academy-sciences-aas-prof-kevin-chika-urama-faas-chief-economist-and-vice-president-african-development-bank-group-79692

- Africa News Agency. (2025). Okello Robert Bob: Creating one million digital jobs for African youth by 2030. https://africa-news-agency.com/okello-robert-bob-creating-one-million-digital-jobs-for-african-youth-by-2030/

- AFD. (2019). African Diasporas: A Partner in Motion. https://www.afd.fr/en/actualites/african-diasporas-partner-motion

- AI4D Africa. (2024). Mapping AI education in African universities. https://ai4d.acts-net.org/ai4d-africa/

- APAC Media. (2024). Fortinet to train 1 million cybersecurity workforce by 2026. APAC Digital News Network. https://apacnewsnetwork.com/2024/09/fortinet-to-train-1-million-cybersecurity-workforce-by-2026/

- AU. (2020). Digital Transformation Strategy for Africa (2020-2030). https://au.int/en/documents/20200518/digital-transformation-strategy-africa-2020-2030

- AU. (2024). Continental strategy for artificial intelligence. https://au.int/en/documents/20240809/continental-artificial-intelligence-strategy

- AUDA-NEPAD. (2024). White Paper: Regulation and Responsible Adoption of AI for Africa Towards Achievement of AU Agenda 2063. Digital Watch Observatory. https://dig.watch/resource/auda-nepad-white-paper-regulation-and-responsible-adoption-of-ai-in-africa-towards-achievement-of-au-agenda-2063

- Becker, G. S. (1994). Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education.

- Boltt, J. (2025). Microsoft South Africa announces the launch of its AI skilling initiative to Empower 1 million South Africans. https://news.microsoft.com/source/emea/features/microsoft-south-africa-launches-ai-skilling-initiative-to-train-1-million-people-by-2026/

- Digital Planet. (2025). Digital Evolution Index 2025. Tufts University. https://digitalplanet.tufts.edu/digitalevolutionindex2025/

- Ecofin Agency. (2024). Vodacom Launches Digital Skills Hub to Train 1 Million African Youth by 2027. https://www.ecofinagency.com/telecom/2011-46159-vodacom-launches-digital-skills-hub-to-train-1-million-african-youth-by-2027

- Elbehri, A. and Chestnov, R. (eds). 2021. Digital agriculture in action – Artificial intelligence for agriculture. Bangkok, FAO and ITU. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb7142en

- EngineerIT. (2023). Cisco and NIL launch Project 525 to train and upskill the next-generation network. https://www.engineerit.co.za/article/cisco-and-nil-launch-project-525-to-train-and-upskill-the-next-generation-network

- Etzkowitz, H., & Leydesdorff, L. (2000). The dynamics of innovation: From National Systems and “Mode 2” to a Triple Helix of university–industry–government relations. Research Policy, 29(2), 109-123.

- FAO. (2023). Fulfilling the promise of African agriculture. https://www.fao.org/family-farming/detail/en/c/380877/

- Fattibene, D., & Manservisi, S. (2024). The Mattei Plan for Africa: A turning point for Italy’s development cooperation policy? IAI Istituto Affari Internazionali. https://www.iai.it/en/pubblicazioni/c05/mattei-plan-africa-turning-point-italys-development-cooperation-policy

- FSD Africa. (2024). Learnings from the FSD Network’s Gender Collaborative Programme (Report of the FSD Network Conference). https://fsdafrica.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/2025-FSD-Network-Conference-learnings.pdf

- GC3B. (2025). Global Conference on Cyber Capacity Building, Geneva. https://gc3b.org/

- GSMA. (2024). The Mobile Economy Sub-Saharan Africa 2024. https://prod-cms.gsmaintelligence.com/research-file-download?assetId=12080&reportId=50121

- ITU. (2023b). Measuring digital development: Facts and figures 2023. https://www.itu.int/hub/publication/d-ind-ict_mdd-2023-1/

- ITU. (2023a). Mobile network coverage. https://www.itu.int/itu-d/reports/statistics/2023/10/10/ff23-mobile-network-coverage/

- ITU. (2024). Internet use in urban and rural areas. https://www.itu.int/itu-d/reports/statistics/2024/11/10/ff24-internet-use-in-urban-and-rural-areas/

- Jobin, A., Ienca, M., & Vayena, E. (2019). The global landscape of AI ethics guidelines. Nature Machine Intelligence, 1(9), 389-399. https://www.nature.com/articles/s42256-019-0088-2

- M.B. Hossain and M. Islam. (2022). Use of artificial intelligence for precision agriculture in Bangladesh, Journal of Agricultural and Rural Research,6(2): 81-96. http://aiipub.com/journals/jarr

- Microsoft. (2025). The value of increasing public sector skills in the age of AI. https://news.microsoft.com/source/emea/features/the-value-of-increasing-public-sector-skills-in-the-age-of-ai/

- Munyati, C. (2025) Accelerating digital inclusion in Africa, Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/accelerating-digital-inclusion-in-africa/#:~:text=As%20of%202023%2C%20mobile%20penetration%20in%20sub%2DSaharan,limited%20locally%20relevant%20content%2C%20and%20language%20barriers

- Nairobi Declaration on AI Education. (2024). Framework for AI workforce development in Africa. https://nairobideclaration.org

- OECD. (2025). Empowering Learners for the Age of AI: An AI Literacy Framework for Primary and Secondary Education. The AILit Framework for primary and secondary education. https://ailiteracyframework.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/AILitFramework_ReviewDraft.pdf

- UNDP. (2021). NextGen Capacity Development: Transforming Capacities for Tomorrow’s Challenges. https://www.undp.org/publications/nextgen-capacity-development

- UNESCO. (2021). Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000381137

- UNESCO. (2023). Global education monitoring report 2023: Technology in education: A tool on whose terms? https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000385723

- UNICEF Nigeria. (2025). Connecting every child to digital learning. https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/stories/connecting-every-child-digital-learning

- UNICEF Zimbabwe. (2024). Expanding access to quality education: The power of digital learning in Zimbabwe. https://www.unicef.org/zimbabwe/stories/expanding-access-quality-education-power-digital-learning-zimbabwe

- WEF. (2020). The future of jobs report 2020. https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-future-of-jobs-report-2020/

- WEF. (2023). How Africa’s youth will drive global growth. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2023/08/africa-youth-global-growth-digital-economy/

- WEF. (2024). Africa’s digital economy: Pathways to inclusive growth. https://www.weforum.org/reports/africa-s-digital-economy-pathways-to-inclusive-growth/

- WEF. (2025). Why AI literacy is now a core competency in Education, World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/05/why-ai-literacy-is-now-a-core-competency-in-education

- World Bank. (2021). Connecting Africa Through Broadband : A Strategy for Doubling Connectivity by 2021 and Reaching Universal Access by 2030. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/131521594177485720

- World Bank. (2023). EdTech Readiness Index (ETRI) Compilation Note. https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/c913b5374a66aff246e5534be62e41c1-0200022023/original/EdTech-Readiness-Index-Compilation-Note.pdf

- World Bank. (2025). Projects & Operations: The World Bank, World Bank. https://projects.worldbank.org/en/projects-operations/projects-home

- Yang, Y., Ye, L. and Feng, Z. (2025) Application of Artificial Intelligence in Medical Imaging: Current Status and Future Directions, Wiley Online Library. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ird3.70008

Related posts:A Strategic Foresight Framework for Digital Transformation in VUCA World | Top Trends Shaping Africa’s Digital Economy in 2025| Innovation Ecosystems: Key to Africa’s Digital Transformation

[…] post: Leapfrogging the Future: How AI can Transform Africa | AI Capacity Building in Africa | Unlocking Africa’s Potential…

[…] ABNT. (2024). The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on African Economies. Retrieved from https://abnt.com/?p=37 […]

[…] Related posts: Bridging the digital divide for inclusive & sustainable developmentReflection on the Digital Transformation Strategy for Africa (2020-2030)…

[…] posts: Bridging the digital divide for inclusive & sustainable developmentReflection on the Digital Transformation Strategy for Africa […]

[…] Related posts: Reflection on the Digital Transformation Strategy for Africa (2020-2030) […]